- Puppet show enchants Children as Boi Mela comes alive on day 2 |

- DSCC Admin Salam’s drive to make South Dhaka a ‘clean city’ |

- 274 Taliban Dead, 55 Pakistan Troops Killed |

- Now 'open war' with Afghanistan after latest strikes |

- Dhaka's air quality fourth worst in world on Friday morning |

UNICEF: Safe, Affordable Housing Is Key to Ending Poverty

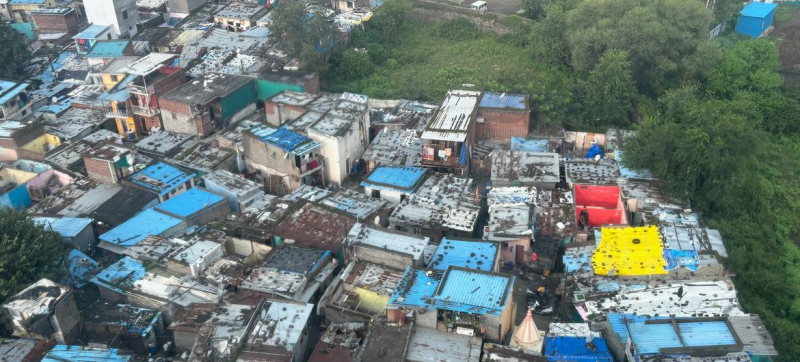

Almost 60 per cent of the population in Mumbai, India lives in slums or informal settlements.

When Denis Jobin, a senior evaluation specialist at the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), visited a slum in Kenya in March as part of an ongoing evaluation, the smell was overwhelming.

Mathare, one of the country’s largest slums, houses upwards of 500,000 people in five square kilometres, cramming them together and storing the human waste they produce in uncovered rivulets. But when he recounted the visit later to UN News, this was not the image that stuck with him the most.

What he remembered most clearly was a group of boys and girls dressed in navy blue school uniforms — the girls in skirts and the boys in pants, both with miniature ties underneath their vests — surrounded by squawking chickens and human waste.

There was no formal, or UNICEF-funded, school nearby. But the Mathare community had come together to create a school where their children might have the chance to break an intergenerational cycle of poverty and invisibility.

“That was a message for me: development should be localised. There is something happening at the community [level],” said Mr Jobin.

Globally, over one billion people live in overcrowded slums or informal settlements with inadequate housing, making this one of the largest development issues worldwide, but also one of the most under-recognised.

“The first place where opportunity begins or is denied is not an office building or a school. It is in our homes,” UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed told a high-level meeting of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) on Tuesday.

Mr Jobin was one of the experts taking part in the High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) on Sustainable Development at UN Headquarters in New York this month to discuss progress — or lack thereof — towards the globally agreed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

One of the goals aspires to create sustainable cities and communities. However, with close to three billion people facing an affordable housing crisis, this goal remains unrealised.

“Housing has become a litmus test of our social contract and a powerful measure of whether development is genuinely reaching people or quietly bypassing them,” said Rola Dashti, Under-Secretary-General for the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA).

With over 300 million unhoused people worldwide, it is easy to forget about the one billion people who are housed but inadequately. These people, who populate informal settlements and slums, live in unstable dwellings and in communities where few services are provided.

“Housing reflects the inequalities shaping people’s daily lives. It signals who has access to stability, security and opportunity and who does not,” said Ms Dashti.

Children living in slums or informal settlements are up to three times more likely to die before their fifth birthday. They are also 45 per cent more stunted than their peers as a result of poor nutrition.

Women and girls are more likely to experience gender-based violence. Human trafficking and child exploitation are also more prevalent.

People in informal settlements are often not part of the national census, according to Mr Jobin, meaning they are not taken into consideration in policies, social programmes, or budgets. Even if they were given social protections, these settlements rarely have addresses where families could receive cash transfers.

This is why experts often say that people living in informal settlements and slums are invisible in official data and programmes.

“You’re born from an invisible family, so you become invisible,” Mr Jobin said. “You don’t exist. You’re not reflected in policies or budgeting.”

This invisibility makes it almost impossible to escape poverty.

“You become a prisoner of a vicious circle that entertains itself and then you reproduce yourself to your kid,” he said, referring to an inescapable cycle of deprivation.

More and more people are migrating into urban centres, leading to the growth of these informal settlements. And with their growth comes more urgency to address the issues.

The World Bank estimates that 1.2 million people each week move to cities, often seeking the opportunities and resources they offer. But millions of people are never able to benefit, instead becoming forgotten endnotes in an urban paradox that portrays urban wealth as a protection against poverty.

By 2050, the number of people living in informal settlements is expected to triple to three billion, one-third of whom will be children. Over 90 per cent of this growth will occur in Asia and Africa.

“These statistics are not just numbers — they represent families, workers and entire communities being left behind,” said Anacláudia Rossbach, Under-Secretary-General of UN Habitat, which is working to make cities more sustainable.

It is not just national and local governments that struggle to contend with informal settlements — organisations like UNICEF are also “blind”, Mr Jobin said, regarding the scope of problems in informal settlements.

Development partners face twin issues in designing interventions — there is not enough national data, and informal governance, or slum lords, can be more critical for coordinating programmes than traditional governmental partners.

“We know the issue … But somehow we have not really been able to intervene,” he said.

Ms Mohammed emphasised that we need to begin to see adequate and affordable housing as more than just a result of development — it is the foundation upon which all other development must rest.

“Housing is not simply about a roof over one’s head. It’s a fundamental human right and the foundation upon which peace and stability itself rests.”