- India Sees 9% Drop in Foreign Tourists as Bangladesh Visits Plunge |

- Dhaka Urges Restraint in Pakistan-Afghan War |

- Guterres Urges Action on Safe Migration Pact |

- OpenAI Raises $110B in Amazon-Led Funding |

- Puppet show enchants Children as Boi Mela comes alive on day 2 |

Early humans climbed trees and made tools with hands

Our hands can reveal a lot about how a person has lived – and that’s true for early human ancestors, too.

Different activities such as climbing, grasping or hammering place stress on different parts of our fingers. In response to repeated stress, our bones tend to thicken in those areas.

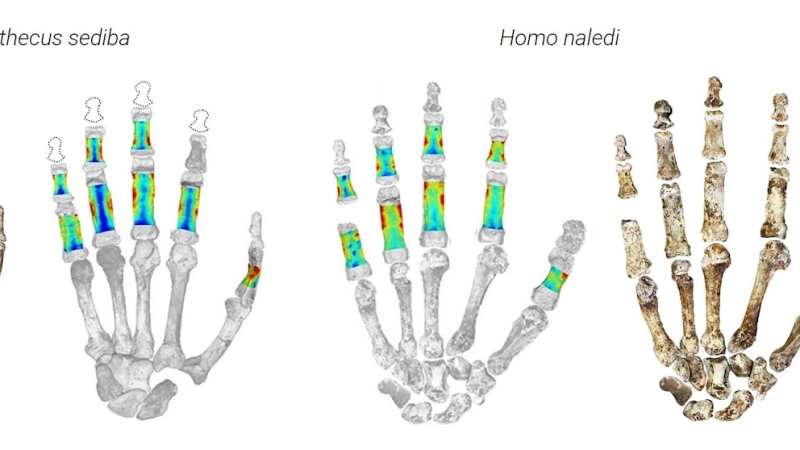

To study how ancient humans used their hands, scientists used 3D scanning to measure and analyze the bone thickness of fingers.

They focused on the fossil hands of two early human ancestor species recovered from excavations in southern Africa, called Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi. The individuals lived around 2 million years ago and around 300,000 years ago, respectively.

Both ancient human species showed signs of simultaneously using their hands to move around – such as by climbing trees – as well as to grasp and manipulate objects, a requirement to being able to make tools.

“They were likely walking on two feet and using their hands to manipulate objects or tools, but also spent time climbing and hanging,” perhaps on trees or cliffs, said study co-author and paleoanthropologist Samar Syeda of the American Museum of Natural History.

The findings show there wasn’t a simple “evolution in hand function where you start off with more ‘ape-like’ and end up more ‘human-like,’” said Smithsonian paleoanthropologist Rick Potts, who was not involved in the study.

Complete fossil hands are relatively rare, but the specimens used in the study gave an opportunity to understand the relative forces on each finger, said Chatham University paleontologist Erin Marie Williams-Hatala, who was not involved in the study.

“Hands are one of the primary ways we engage with world around us,” she said, reports UNB.