- Israel Strikes Tehran with US Support Amid Nuclear Tensions |

- India Sees 9% Drop in Foreign Tourists as Bangladesh Visits Plunge |

- Dhaka Urges Restraint in Pakistan-Afghan War |

- Guterres Urges Action on Safe Migration Pact |

- OpenAI Raises $110B in Amazon-Led Funding |

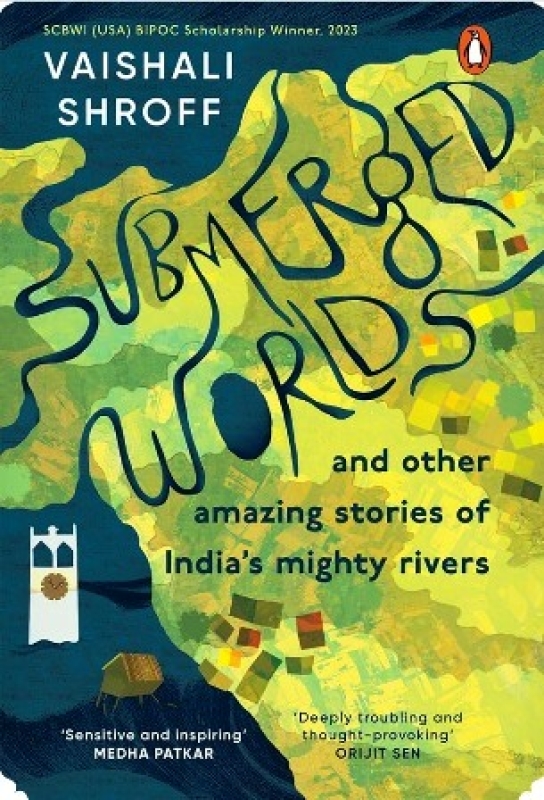

Submerged Worlds & Amazing Stories of India’s Mighty Rivers

Book Review: April 28, 2025. SANDRP

Submerged worlds and amazing stories of Indias mighty rivers, Book Review: April 28, 2025. SANDRP

“All rivers are living entities. The job of any river is to flow. And it flows in a most systematic and sophisticated manner. As it flows, it nurtures everything around it, everything within it. A flowing river, whether it’s gurgling, bubbling and frothing on rocks and cobbled valleys or silently meandering along its course on the plains, is a happy and healthy river. Like a lap of a mother, the river allows many living beings to make a home and live together…” These introductory lines from the recently published book “Submerged Worlds and Amazing Stories of India’s Mighty Rivers” highlights the significance of a free-flowing river.

The 2025 book (pages: 221 + xxiv) by the author Vaishali Shroff (Published by Penguine Random House India) documents the disturbing realities of our once vibrant but now dammed and damaged riverscapes in an informative manner. The author accepts for not being an expert on the subject. It was just an exposure to the submerged villages in the Tehri dam, Uttarakhand that motivated her to explore more on how poorly planned development activities have adversely affected the rivers and the dependent communities across the country. This common element has resonated well throughout the book. It is great to see that well known social activist Medha Patkar has written forward to the book.

The book revisits the struggles of these dammed rivers and drowned communities, highlighting the injustices they have endured for decades. It prompts us to question why we continue to overlook more viable alternatives, especially when most dams have entirely failed to achieve their intended goals.

The author also vividly shares the tale of the pristine rivers which are of late succumbing to relentless pollution, unsustainable development projects, rapid urbanization grabbing their floodplains & banks. The book further presents the glimpse of looming climate change threats on the Indian rivers and people.

The stories of cruise tourism, waterway plans in lower stretches of Ganga amid growing pollution and the developmental project in the Great Nicobar Islands creating existential crisis for fisherfolks and still undocumented rivers & uncontacted tribes of the island are quite disturbing.

At the same time, the description of Rabari tribe of Jawai River in Pali district, Rajasthan and Warli tribe along Dahisar river in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Mumbai who are still living in peaceful coexistence with the natural world around including the river, forest and wildlife sounds unbelievable as well as encouraging.

Along with numerous dying and polluted rivers and aggrieved communities of India, the author also wades through a few remaining clean rivers of the country like, the Dwaki (Umngot) in Meghalaya and the Chhimtuipui in Mizoram concluding: “Good thing happens when we leave our rivers alone and give her more than we take from her. For she demands nothing more than just some freedom for space to flow.”

Should we invest resources to bring back extinct rivers like Saraswati or address the plight of existing but threatened rivers like Yamuna and Ganga is another important point the author has raised.

The book lists various acts, rules and projects aimed at the cleaning and conserving the Indian rivers and reasons why despite all the plans and measures, they remain in ruins with bleak future.

Further, dealing with the nomenclature, the author advocates for greater role for women in river governance affairs in India. Before ending, the author writes about the Rights of the Rivers (it is not clear how this is going to help the cause of rivers) and Dam Decommissioning concepts being acknowledged and implemented globally can be helpful in addressing the degradation of our rivers.

There are tales not just of despair but also of the inspirations coming from remarkable efforts being done by several experts, activists, community and civil society groups to protect and raise the voices of our rivers and communities relying on them. The author also suggests small steps which individuals and society as whole can initiate in reversing the trend.

Shortcomings: The book has some major flaws and mistakes which require corrections. For example, it wrongly mentions the Godavari, Kaveri, Tunghabhadra, Krishna, Narmada as rain-fed and seasonal (page 2). The claim that glaciers contribute towards two-thirds of Earth’s water supply (page 12) is incorrect.

Stating that Gangaputras of India live (only) in Varanasi (page 21) is also not right. And Brahmaputra and Son are not the only two Indian rivers with masculine names. There are many rivers with male names in India including Lohit, Damodar, Barakar etc.

Though the author extensively decribes the threats from melting glaciers and climate change (e.g. P 16), the author fails to mention about increasing impacts of Glacier Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF) on Himalayan rivers and local people especially in the context of October 2023 GLOF disaster which left about 55 people dead, 74 missing and washed away the massive Teesta III dam and damaged several other hydro projects on Teesta River in Sikkim and North Bengal.

The book also suffers from inadequate research and contradictions. Amid several examples of dams damaging the river eco-systems and while supporting the cause of free-flowing rivers, the author appears praising Jawai dam -among biggest ones in Western Rajasthan- which has greatly compromised the natural flows of the Jawai River and contributed in turning the river seasonal and is further threatened by the proposed 640 Mw Sirohi pump storage project.

Similarly, given the adverse impacts of already built dams, rampant sand mining, increasing pollution, destruction of ravines and ongoing Parbati-Kalisindh-Chambal river interlinking project endangering the rich aquatic life of Chambal rivers, listing the Chambal among cleanest rivers of India needs a relook.

It’s not just the legislations but the institutions governing the rivers have miserably failed. Moreover, the role of judiciary has not been satisfactory. The book grossly misses on these important aspects. The other important topics of inland waterways, river interlinking plans, river front projects and riverbed mining require more details.

The book totally skips discussing the impacts of increasing plastic, anti-biotics and heavy metals pollution in the rivers. Though, the narration is moving but there are too many mythological references and at times the sudden change in context breaks the pace.

It looks incomplete in the absence of stories of how Pune citizens and Vadodara activists have been striving hard to protect the Mula-Mutha and Vishwamitri rivers respectively. There are many more amazing and troubling tales of the violated and endangered Indian rivers and people which must be documented. Wish the book could have covered some more of these untold stories.

The central message the book conveys is that though the Indian rivers and riverine people are presently dammed and drowned but their spirit stays undefeated and undeterred. And the author loudly emphasis on the importance of free-flowing rivers.

“Call a river nadi in Sanskrit, Flumen in Latin, potami in Greek, rio in Portugues and Spanish, rivier in Dutch, be` in Chinese or darya in Urdu. Call a river by any name in any part of the world and all it wants to do is flow, free of selfish and excessive human interventions.”

Overall, the stories are educative, engaging and disturbing too. The author has made sincere efforts in investigating the diverse worlds of Indian rivers. Despite the limitations (we hope care is taken to remove them before it goes for print again), it’s a worth reading for school students and other readers to learn and inquire more about our rivers. We hope it also motivates all to take timely actions to protect our rivers from dams, pollution and unjustifiable developmental projects.

Bhim Singh Rawat (bhim.sandrp@gmail.com)